In this essay I am diving deeper into my own comics, comparing the intended representations to the representation that I ended up creating. The ideas used in this essay are mostly based on The Media Insider video of Stuart Hall’s representation theory and sources I found while researching the subject of representations further (all sources listed at the end). I was also very inspired by a video from Last Week Tonight with John Oliver about how the police are represented in media. The video led me to finding an article about how representation of police in “cop dramas” affects public views on police use of force.

Representation matters

As a comics artist and writer representation is something that I have discussed and that has been discussed about my work many times. My comics Immortal Nerd and Life Outside the Circle have even been topics for academic discussion about representation of queer characters in media (see. Vuorinne & Kauranen; Kauranen et.al.). For me the start of trying to create better representations came from Tumblr (a blogging service/social media) where I read and followed many feminist media blogs. Unfortunately I no longer remember who on Tumblr had wrote the following thought on a blog post, but it changed the way I see my art forever. The blogger said that in a lot of media the default character is a white cisgender able-bodied straight man. If the character doesn’t have to be for example a woman — maybe to be someone’s mother — the character defaults to a man. The blog post opened my eyes and I decided to fight against this in my own art. I decided that my characters will no longer be white cisgender able-bodied straight men unless they have a reason for it — maybe to be someone’s stereotypical father.

I have kept this method for creating characters to this day. In my current webcomic Millenials Kill I can count the white cisgender able-bodied straight men on one hand, more precisely one finger. There’s exactly one character that fits the bill, Bill Hurder, a man who will kill and murder.

Let’s talk briefly about Stuart Hall’s representation theory and then get back to analyzing my webtoon comic that has created the most discourse, Immortal Nerd. I of course suggest every reader to go watch the video linked above, but in short, Hall’s theory examines how meaning is constructed and interpreted in media. For example, a journalist might write a story about a politician, representing her as “a bossy bitch” when someone else might describe her as a good leader. These different representations don’t just exist in a vacuum, but they aim to create meanings. (The Media Insider.) In 2015 when I first started drawing the comic Immortal Nerd, I wanted to draw a diverse world where one’s race, ethnicity, gender, sexuality, or other identities wouldn’t affect the outcomes of the character’s lives. I wanted to draw a utopian world with “good” representation that refused to build on stereotypes and create negative meanings on marginalized characters. I used my method of defaulting to anything else than a white cis man and created characters that are as varied as possible. The genders and the lack of them was something the webtoon audience hadn’t seen before. That’s evident from the fact that even the leg hair of the ambiguously gendered main character stirred a debate in the comments episode after episode.

In an article called “ungendering fashion”, Clark and Rossi talk about how the term “transgender” finally entered the public discussion on USA in year 2015 (201). This was the same year when the USA based publisher LINE Webtoon started publishing my weekly webcomic series Immortal Nerd. Looking back at my own work with the lens of Clark’s and Rossi’s article I can see a lot of the same ungendering/transgender discussion happening in my own work. I believe this discussion to also be one of the reasons why my comic was chosen to be published. It was trendy and current with its gender non-conforming characters and wacky situations that turned gender stereotypes upside down. Like Ralf Kauranen once said while interviewing me in the Helsinki Comics Festival, in this comic even the cat is named dog. (This refers to a cat character who’s named after a popular meme dog, doge.)

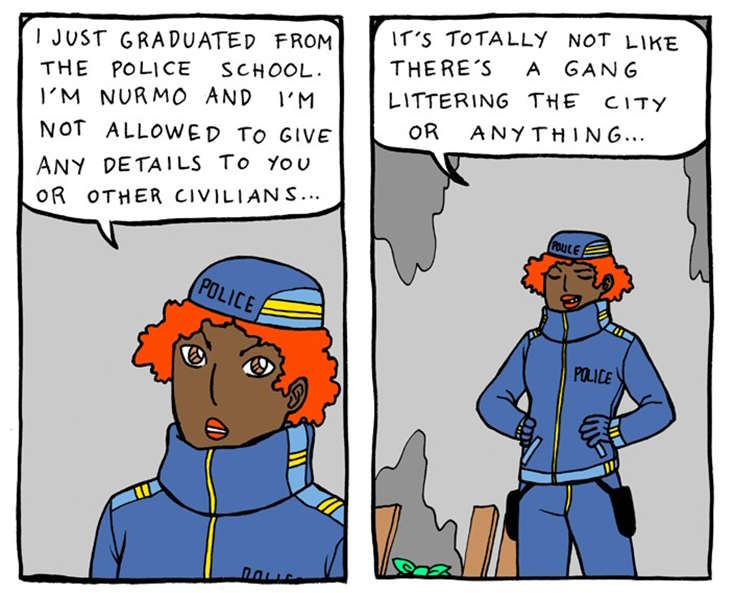

This kind of utopian thinking was good for a humorous sci-fi comic, but even if I was aiming to build positive diverse queer representations, I was also building all new stereotypes and failing to avoid others. For example, my representation of a police officer aligned perfectly with how the American media often wants to represent police officers — not as people with power, but as normal people who want to help. Donovan and Klahm discuss this in their article about their research on how “cop dramas” affect the general perception of police use of force. They go on to describe that people who regularly watch fictional entertainment media about police work are more likely to believe that police are successful at lowering the crime rates, they don’t make serious mistakes, and that police had a “good reason” for the force they used (8–10).

Stereotypes are often linked to power imbalances in the society (Lips, 2019, 59–62). Even if back in the year 2015 I though my police character Nurmo was a great “girlboss” representation, in my current opinion portraying a police officer in a way that doesn’t acknowledge the immense power they hold in their hands — the power to even end another person’s life — can be detrimental to society at large. If power goes unchallenged or even celebrated, the use of power can escalate.

How to create better representation?

Sensitivity readers, alternatively known as authenticity readers, are individuals with personal, lived experience of the subject matter (Lawrence). In comics sensitivity reader helps the author by reading the story from their own point of view and giving feedback and recommendations that can help make the representation more realistic or to decrease unintended microaggressions in the comic. In my work as a comics artist and as the chairman of the Finnish Comics Society, I have witnessed the emergence of sensitivity readers in comics publishing.

The subject of sensitivity readers has also sparked a division among authors, readers, artists and publishers. One argument is that employing sensitivity readers in the editing process ruins creativity and forces restrictions on the story (see Rosenfield; Kirka). The other argument is that it is a handy tool that gives great feedback to the author, making it possible for them to make their work even better (see The Bookseller; Ireland). I see sensitivity reading as a great tool for making comics with “better” representations of marginalized people. Sensitivity reader isn’t working to change the work into something it’s not trying to be, but rather find the things that can make the work align with the author’s intentions better. In my experience this doesn’t differ much from the normal editing process a published comic goes through. Sensitivity readers also make it possible for authors to make stories about groups of people they don’t belong to themselves.

The discussion around “#OwnVoices” storytelling also has two camps. #OwnVoices means, that the author who makes the story belongs to the group the story is about, for example, a disabled person writing about a disabled character. The term was originally coined by Corinne Duyvis in 2015 as a short hashtag that can be used to promote books that were written by and for marginalized people (Lavoie, 2021.) The first camp believes that one shouldn’t write about a marginalized group unless they belong in it. The second group believes that anyone can tell diverse stories and learn more about different marginalized groups while making stories about them. #OwnVoices was also criticized for posing a danger to the authors labeled with the hashtag (Lavoie, 2021). The hashtag reveals information about the author leaving them vulnerable to attacks from malicious online groups. My own view on the issue is that anyone should be able to tell stories about minorities and the use of sensitivity readers while editing the story can help immensely. At the same time I understand that the need for the hashtag came from a situation where marginalized creators find it very difficult to find publishers. Normative already mainstream creators get paid to tell the stories of the authors who will never even see an email reply from a publisher.

To answer my question, how to create better representation, I’m replying just “editing”. I believe that listening to feedback and challenging one’s own thinking is the way to create better works. I also believe that the “mistakes” I feel that I made while drawing Immortal Nerd were part of my path towards becoming a better artist and critical thinker.

This text was originally written as a part of a learning diary for a Gender Studies course. The original version has been altered and expanded to touch on my own art and the representations in it even deeper. The original version was written in 4.3.2024.

References

Clark, Hazel and Leena-Maija Rossi. “Clothes Unmake the (Wo)man: Ungendering Fashion (2015)?” Crossing Gender Boundaries: Fashion to Create, Disrupt and Transcend. Ed. Andrew Reilly and Ben Barry. Bristols: Intellect, 2020, 201–218. Web.

Donovan, Kathleen M., and Charles F. Klahm. “The Role of Entertainment Media in Perceptions of Police Use of Force.” Criminal justice and behavior 42.12 (2015): 1261–1281. Web.

Ireland, Justina. “Goodbye, Sensitivity Readers Database” https://medium.com/@justinaireland/goodbye-sensitivity-readers-database-e1cbc53044a9. 26 Feb. 2018. Web. 5 Dec. 2023.

Kauranen, Ralf, Leena Romu, and Anna Vuorinne. ”Vähemmistöt ja moninaisuus nykysarjakuvassa.” Synsygus. Suomen uskonnonopettajain liitto ry. 2/2023, (2023): 10–14.

Kirka, D. “Critics reject changes to Roald Dahl books as censorship.” https://apnews.com/article/books-and-literature-roald-dahl-business-entertainment-91c9bb1a7a10392abeef6feec3159e8b. 19 Feb. 2023. Web. 5 Dec. 2023.

Lavoie, Fin. (2021) Why We Need Diverse Books Is No Longer Using the Term #OwnVoices. Online: https://diversebooks.org/why-we-need-diverse-books-is-no-longer-using-the-term-ownvoices/

Lawrence, E. E. “Is Sensitivity Reading a Form of Censorship?” Journal of information ethics 29, no. 1 (2020): 30–44. Web.

Last Week Tonight. “Law & Order: Last Week Tonight with John Oliver (HBO).” https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=DNy6F7ZwX8I. 12 Sep. 2022. Web. 15 Feb. 2024.

Lips, Hilary M. Gender: The Basics. Second edition. Vol. 1. Oxon: Routledge, 2019. Print.

Rosenfield K. “Rise of the sensitivity reader.” Reason. 54:4. (2022): 46–49. Web.

The Bookseller. “Publishers defend sensitivity readers as vital tool following author criticism.” https://www.thebookseller.com/news/publishers-defend-sensitivity-readers-as-vital-tool-following-author-criticism. 20 Jun. 2022. Web. 5 Dec. 2023.

The Media Insider. “Stuart Hall’s Representation Theory Explained! Media Studies revision.” https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=yJr0gO_-w_Q. 8 Nov. 2019. Web. 15 Feb. 2024.

Vuorinne, Anna, and Ralf Kauranen. “Visions of Queer Places: Migration and Utopia in Finnish Queer Comics.” European comic art 15.1 (2022): 26–45. Web.